My life so far

Youth

A small white blanket spread out on the living room floor, a blue box filled with Lego bricks, and endless possibilities—this is the first vivid memory of the child I once was.

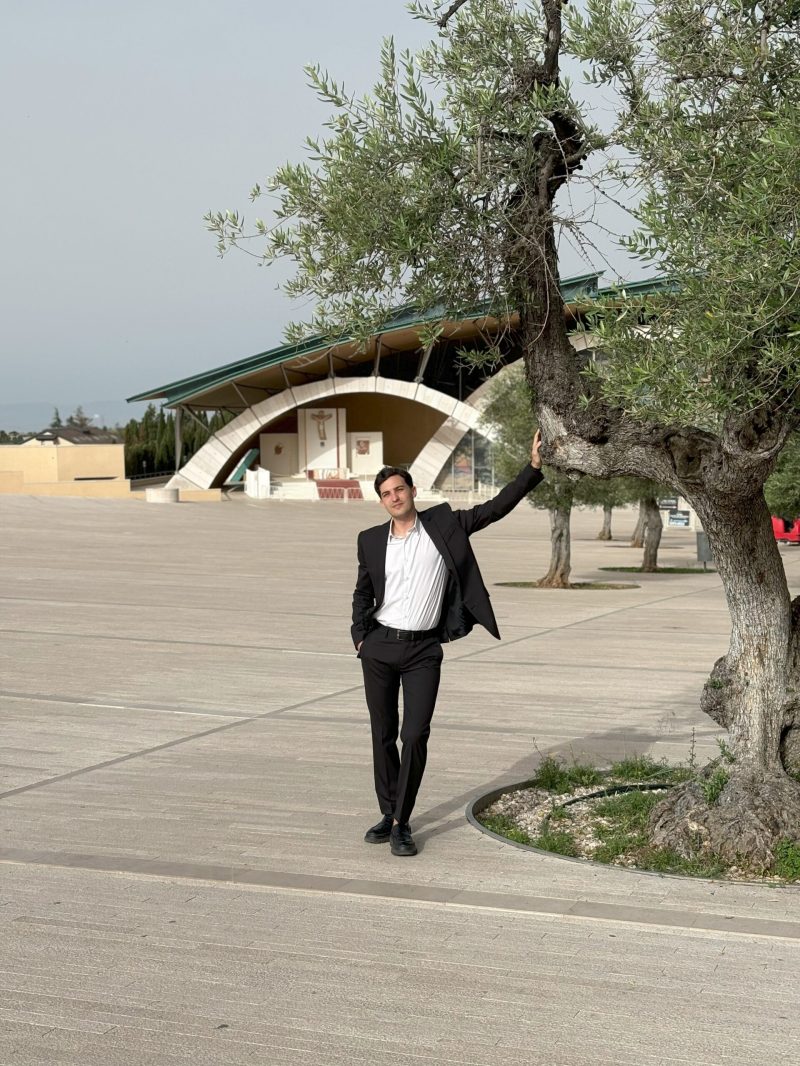

I come from San Giovanni Rotondo, a small town in Puglia known to the world through the deeds of a man who became a saint, Padre Pio. His acts have been a beacon for many, but for me, the most precious legacy he left is the lesson that every place, however humble, can shine with its own light.

“Viale dei 40 metri” leading to the Sanctuary of Padre Pio

Mine is a modest family. The house in which I was born and raised was built by my grandfather Michele, a bricklayer by trade. He emigrated to France in search of better work opportunities, using his days off to return to his hometown and build his future home, dreaming of an eventual return. Brick by brick, after more than a decade, he achieved his goal. From him, I first learned the meaning of sacrifice, hard work, and perseverance. As the philosopher-emperor Marcus Aurelius teaches, what is done with patience and dedication endures.

Grandfather and Grandson, “Michele Pompilio”

During my early school years, I often spent time at the neighborhood parish, a gathering place for children of all ages, where friendship and serenity flourished. Among the many faces of that time, I remember Roberto with great affection—a robust, bearded man with a kind heart who dedicated his adult life to mentoring young people. I am often reminded of his good-natured smile with which he scolded me because I used to sneak off at the time of Mass. Simple lessons, yet they profoundly shaped my sense of community and responsibility.

The days of my childhood flowed carefree, especially in summer, when time seemed to stretch. It was the season when families who had moved abroad—to France, Germany, or Northern Italy—would return. I befriended their children, introducing them to our games, sharing moments I like to think they carried with them as small treasures.

One of my fondest memories from that time is about my father, an architect. He would often sketch objects from our home, and my younger brother and I would compete to guess what they were. Those games became my first lessons in observation and imagination. From him, I learned the value of excellence and attention to detail. “Beauty will save the world,” wrote Dostoevsky, and my father, through his work, taught me that beauty is born from passion and precision. Some of his sketches contributed to the creation of this company, and to this day, he remains my source of guidance, inspiration, and reflection.

Michele, first from right, with his family

I belong to the generation that gradually witnessed the arrival of mobile phones, the first online chats, and the shrinking of distances. At ten years old, I received my first mobile phone—I used it to download songs and exchange messages. Today, I recognize the immense opportunities these technologies offer, but I also believe balance is essential. Epictetus understood this long ago when he said that things in themselves are neither good nor bad; it is our use of them that determines their value.

I often reflect on how objects evolve and how innovation reshapes our lives. Nowhere is this more evident than in the world of design. Plexiglass, originally developed for aeronautical and automotive applications, has become a staple for tables, chairs, and lamps. Stainless steel, once reserved for industrial and medical use, has found its place in furniture thanks to visionaries like Maria Pergay. Every material tells a story of transformation, a testament to human ingenuity’s ability to reinvent the world.

I often joke with my peers that our adolescence was a happy burden: the slow pace of the country and the serenity made us experience moments of pure joy, so intense that everything that came after seemed to taste bittersweet. A notion frequently echoed in the writings of great thinkers, primarily Seneca, is that “true wealth is not in having much, but in desiring little” and perhaps, in that simplicity, we were indeed rich.

University Studies

I always envied my brother, four years younger, for his confidence in knowing what he would do in his working life. Since childhood, he pursued his dream of becoming a doctor with unwavering dedication. Watching him devote himself to his goal was a constant source of inspiration.

As for me, I cannot pinpoint the exact moment I decided to study engineering. I had developed an affinity for the sciences, believing they held the great truths of the universe. Fascinated by the masters and inventors of the past, I was curious about how the world worked—not just in terms of objects, mechanisms, and processes, but also the systems humanity has built over the centuries, from law to economics.

Seeking a field that combined my interests, I discovered a program that blended engineering and economics. The decision was made, and I set off for Bologna—timid, apprehensive, but eager for knowledge and adventure. There was no specific reason why I chose this city; it was likely a combination of factors: the university’s reputation, its location, and perhaps my mother’s influence, as she had once studied there before pausing her education due to my impending arrival.

Those years in Bologna became deeply cherished, transforming the city into my second home. Beyond academic learning, the most valuable gift I received was the intricate web of human and social connections. I was fortunate to meet many diverse individuals, each with their own story, ideals, and worldview. I formed friendships that remain strong, despite the physical distances that now separate us.

Our home became a meeting place for university friends, often hosting lively dinners. I loved the dynamic atmosphere—it radiated a zest for life.

Michele in his twenties in the university apartment.

Balancing lectures and study sessions with the city’s vibrant social scene, I approached my education with a mix of diligence and strategic prioritization. At the start of each semester, I carefully chose which classes to attend and which to skip, reclaiming precious time for personal pursuits.

It was during these years, as I mingled with peers from more humanistic disciplines, that I began to really discover the philosophers of the past: starting with Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and then Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, St. Augustine, passing through Pico della Mirandola, to the more recent Jean-Paul Sartre and Nietzsche. Almost for fun I began to read them too, as if to balance the rationality of my studies. Their writings fascinated me and I found in them a usefulness that is still with me today.

During this period, an opportunity arose to study abroad. Among the options, Buenos Aires, Argentina, stood out. I thought, “When will I ever have another chance to go there?” and applied. At the dawn of my third year, I embarked on a four-month journey to Latin America.

Obelisk of Buenos Aires in Plaza de la Republica

The city of Buenos Aires, with its three million inhabitants, is a melting pot of South America. Defined by vast avenues, lush greenery, and architectural masterpieces, it revealed to me the profound contrasts of the world—wealth and poverty, ostentation and humility, despair and faith. The middle class seemed almost nonexistent: some had everything, others nothing. I met people from both extremes, yet stripped of their circumstances, I would not have seen any difference. I found shared ideals and thoughts—more similarities than divisions.

Upon my return, the outbreak of the pandemic disrupted the delicate balance of life. Existence came to a halt for an instant, only to adapt and resume its course. Uncertainty bred fear, and like many, I sought refuge within the familiar walls of my family home.

That period was bittersweet: while it deprived me of moments of my youth, it granted me the gift of time—time to spend with loved ones, whom I had gradually neglected, absorbed as I was by the intensity of my experiences. In those days, I delved even deeper into philosophical writings, which had by then become steadfast companions, offering solace in the darker hours.

And so, after a mere blink of an eye—one that could have lasted a second or a century—life slowly began to rise again, though leaving us profoundly changed.

It was during this time that I obtained my first bachelor’s degree and embarked on my master’s studies. Yet life in Bologna was not the same, still bearing the lingering traces of past misfortune. A year passed, and I realized the moment for change had arrived.

Work

At twenty-two, while still pursuing my studies, I decided to take my first steps into the working world. I liked the idea of earning something on my own, gaining a sense of independence.

But among all the possible paths, which one would I have truly enjoyed following? The answer was unclear, yet one thing was certain: whatever choice I made, I wished to contribute to the good of people, to the beauty of creation, and to human progress.

I was particularly fascinated by the world of fashion and design. I deeply believed in creativity and the excellence of Italian craftsmanship, which had made its way across the world thanks to its mastery.

At the end of the summer, I set out in search of an opportunity that could open the doors to that world that so captivated me. Through an acquaintance, I heard excellent things about a company in Belluno, a leader in the eyewear industry: EssilorLuxottica. Already familiar with it through some of my studies, I decided to apply for an internship. The response came swiftly and after a few interviews I have been hired in the Quality department of a plant producing prescription lenses, and so I departed for the Dolomites.

EssilorLuxottica plant in Agordo (BL)

Describing the atmosphere of that place is no easy task. Towering mountains, icy winters, cutting-edge technology, and an unwavering dedication to work. I could hardly believe I had found myself in a company that, thanks to the vision of a man like Leonardo Del Vecchio, had built something so extraordinary. Thousands of employees, most of them from those very lands, who in turn gave back to their community the commitment it had invested in them. The symbiosis between the company and the territory was tangible, harmonious.

I hold dear the memory of my mentor, Luigino—a man of vast experience, stern in manner yet kind at heart. He saw in me a young novice and always extended his support in difficult moments. In return, I repaid his trust by applying what I had learned during my studies.

With over thirty years of experience, Luigino taught me the true meaning of the dignity of labor, of effort, and of respect for people. One particular episode still echoes in my mind: one morning, at 8:00 AM, I was having a coffee in the break area while production was already underway. For this, I was reprimanded, and at the time, I did not take it well. I felt diminished, as if my studies somehow set me apart. Only now do I recognize the arrogance of such a thought and the lack of respect for the value of the work unfolding around me.

What was meant to be a formative experience turned into nearly two years, during which I completed my studies. Though I was satisfied with my job, my colleagues, and the experience I was gaining, I never truly adapted. My personal life was unfulfilled, and solitude was softened only by the company of my books.

So, I began to look around, and soon an opportunity arose at Fendi—a company whose history I had always admired and which embodied many values dear to me: craftsmanship, beauty, heritage, family. Thus, I moved to Florence, cradle of the Renaissance, where the company had established its new production site. I worked in Quality, overseeing jewelry, home accessories, textiles, and eyewear.

Fendi facility in Capannuccia (FI)

Unfortunately, it did not take long for me to realize that the great company it once was had become merely a shadow of its former self. I believe that, once sold, Fendi—like many others—was transformed into a mere profit-generating machine. I do not mean to imply that profit is inherently wrong; rather, I align with the vision of another industry great, Brunello Cucinelli, who speaks of “Humanistic Capitalism,” where ethics and dignity walk hand in hand with the creation of value.

As Karl Lagerfeld once said: “To evolve without ever forgetting who you are—that is the true key to success.” Perhaps the company that once hosted him had lost that key.

An inner unease took root within me, and each day the certainty grew stronger that this was not the right place for me. Instead, I longed to go where I could create something new, something beautiful. Because, as Nietzsche would say, “He who is lost to the world creates his own world.”

And so, just like Padre Pio, who left Pietrelcina for San Giovanni Rotondo to heal his ailments, I too returned home, to heal mine.

Sanctuary of San Pio da Pietrelcina, designed by architect Renzo Piano

The Birth of the Company

The thought of a thread weaving together the concept of home with my grandfather, who built them, my father, who designed them, and myself, who furnishes them, has always fascinated me.

My return home was rather unexpected, as I made the decision without forewarning my family. I settled in an old shop, once my mother’s grocery store, and transformed it into my studio. There, I spent my days drawing, reading, and studying. I had a clear vision of what I wanted to do, but I felt the need to bring order to my thoughts, to untangle the labyrinth of my mind.

Michele in his repurposed studio

I have always believed that to create a product of the highest quality, one must understand every variable that composes the puzzle: materials, processes, people. And to achieve this, I needed to work with raw materials firsthand, to bring my ideas to life with my own hands. So, I visited a metalworking company, where Matteo and his son Giovanni carried on the family trade. I asked if I could learn the craft, and with great generosity and selflessness, they accepted my request. And so, from engineer, I became a blacksmith.

I spent a long time with them, mastering metalworking techniques. With scraps of material, I embarked on creating my first chair. I am not ashamed to admit that it took me a full 19 hours to complete. I refined every piece with the utmost care, ensuring every measurement was precise, every detail flawless. The satisfaction was immense, and to this day, that chair remains in my studio as a symbol of dedication and passion.

The first Chair

During that period, I also allowed myself a fair share of idleness—something I consider fundamental and to which I extend thoughts of gratitude. I believe that idleness, when it does not slip into indolence but is accompanied by awareness, becomes fertile ground for both mind and spirit.

It was not long before I found myself managing my first commission, entrusted to me by a friend, Antonio, who asked me to create four chairs for his insurance agency. How true Epicurus’ words ring: “Of all the things which wisdom provides to make us entirely happy, much the greatest is the possession of friendship.”

Now, borrowing the words of Pico della Mirandola in his Oration on the Dignity of Man, I say to you: as judgment is passed, let not the years of the author be counted, but rather the merits or faults of his work.

I consider myself a disciple of the teachings of the forefathers—both those close to me and the great thinkers of the past, custodians of knowledge and wisdom, in whom I joyfully find answers to my questions

I believe in a future where the dignity of labor and skilled craftsmanship will give birth to new worlds—beautiful, authentic worlds, in harmony with both humanity and creation, where the notion of justice serves as the ultimate measure of all things. And with them, new values for new worlds.